It’s slug season, folks – my least favorite time of year. Those slimy corpulent snakes are munching their way through my vegetable patch, hiding under every bluebell leaf, even leaving silvery trails through my living room at night. How they’re getting in, I’ll never know, but it’s not their being here I’m worried about; it’s my dog, Neptune.

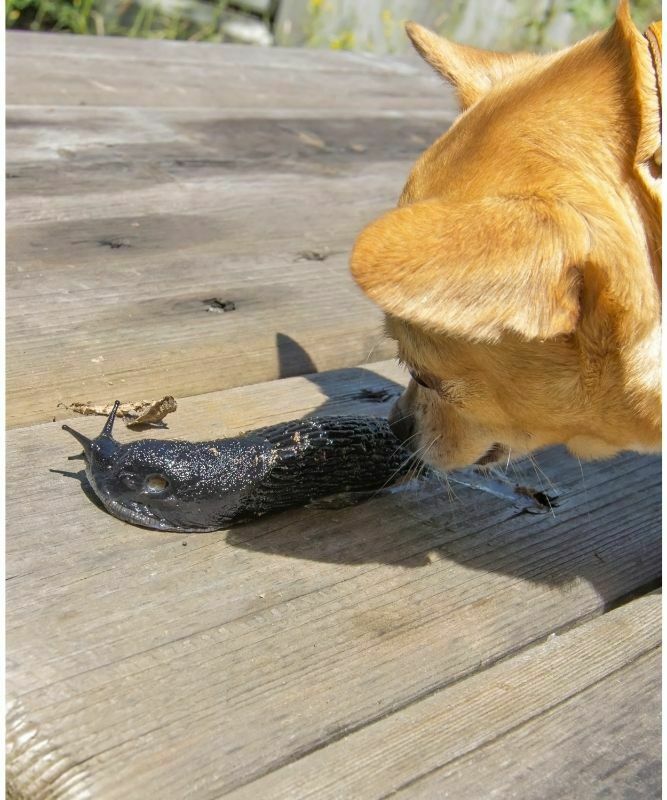

Neptune is a sniffer, and sniffing leads to licking, and licking leads to gobbling things up. He might not pay them any mind outdoors, but my worry is that with them entering the house, he might eat them due to their being in his territory or thinking they’re a special sort of slimy snack.

Now, I know that slugs are considered a delicacy in some parts of the world, but I’m also aware that recently, a young man in New Zealand ate one on a dare when he was drunk. Not long after, he sadly passed on. So, I’ve taken it upon myself to do the research and ascertain whether I should shield Neptune from these intruders.

So, Are Slugs Poisonous to Dogs?

Before I dive into the subject in more detail, I thought I’d answer the question as directly and quickly as possible. Yes, slugs can indeed kill our dogs, but it’s not because they’re poisonous as such.

You need to teach your pooch to avoid slugs because they’re often carriers of a parasite known as rat lungworm – two words you never wanted to read in a row, huh? Just saying it makes me feel a bit queasy, and knowing my Neptune is a risk doesn’t bear thinking about.

As far as my research has shown over the last month or so, the only slug that’s inherently toxic is the sea slug – or certain subtypes of them, anyway. So, be wary if you’re heading for a day at the beach full of poochie paddling.

What the Heck Is Lungworm?

As mentioned above, lungworm is a type of parasite. It starts as a larva, penetrates the intestinal wall, then migrates through the bloodstream to the lungs or respiratory tracts, where it takes residence.

Once safely ensconced within the breathing anatomy of a vertebrate, the larvae then develop into an adult lungworm and reproduces, hatching infected larvae of their own.

The infestation triggers severe inflammation of the host’s airways, gradually destroying respiratory health. Once the larvae have reached a certain point in their infancy, the respiratory irritation causes the host to cough, at which point the larvae are ejected from the airways and swallowed into the digestive system.

The lungworm life cycle starts over after finding an exit from the host via their fecal matter. It’s harrowing stuff. I wouldn’t wish this sort of insidious and disgusting fate on my worst enemy, my world’s best friend.

Is it Just Slugs You Should Be Worried About?

Unfortunately, slugs aren’t the only way your dog can become infected by the lungworm parasite. As gross as you may find them, it’s important to note that although they carry the parasite, slugs aren’t technically to blame.

In this scenario, slugs are what’s known as an intermediate host, meaning they unwillingly help to proliferate the parasite. It’s not something they’re born with. In a way, they’re victims of this awful creature too.

Something I think is especially important to keep in mind is the term “intermediate host.” They’re passing them on, not just directly to animals, but to various locations. Sometimes larvae will get off the slug express in a puddle, in some blades of grass, or even just into their slime trail.

In light of this, we need to keep our dogs away from slug anything! If you see them chewing grass, stop them immediately, never let them drink from puddles, and keep them away from the residual slime trails of slug activity on your property. In fact, I think it’s best we never give our woofers garden time unsupervised during slug season.

One final thing to be aware of is that slugs aren’t the only intermediate host these larvae seek out to get from A to B. They’re also partial to hitching around in frogs and toads, so if you have a pond in your yard, take extra care.

Is Lungworm Contagious?

I’m happy to report that lungworm cannot be passed on from dog to dog or from dog to human. Of course, it’s a tragedy if you know a dog infected with lungworm, but we can take solace in the fact that it will not trigger a pandemic.

That said, with every infected dog, the chances of other dogs that inhabit the same environment catching it do rise. Remember when I mentioned that the larvae use an animal’s stool to make their way back into the world? Well, once they’re free, they’re able to infect another creature, and the more of them there are in a certain area, the higher the chances of infection.

As a result, if you’ve had one case of lungworm on your property, you need to be extra careful to prevent it from happening again. It might even be worth cutting out garden time zoomies indefinitely.

How Do You Know If Your Dog Has Lungworm?

There is no shortage of symptoms when it comes to lungworm infection, which can make it incredibly tough to diagnose. They can all be traced to a different doggy ailment, confusing owners and vets alike until it’s too late.

Let’s run through them here now so you’re prepared for a worst-case scenario…

- Behavioral changes

- Breathing difficulties

- Coughing

- Coughing up blood

- No appetite

- Nose bleeds

- Diarrhea

- Red eyes

- Seizures

- Lethargy

- Weight loss

- Vomiting

- Anemia

The…not-good…but the helpful thing about these symptoms is that each one warrants a trip to the vet, which means you have the best chance of getting your fluffy child the help they need as soon as possible.

Does Breed Play a Role in Susceptibility?

No one really understands why, but Spaniels tend to have a higher risk of lungworm infection than other breeds. Some believe it’s down to genetics, some may just chalk it down to statistical coincidence, and others may simply believe spaniels are more curious than other breeds.

Puppies and young dogs have a higher risk of infection for the same reason. They’re just so dang inquisitive. They want to sniff it all; they want to roll in it all; they’re trying to develop an understanding of the world around them mostly via taste and smell. Sadly, in this instance, curiosity may not just kill the cat but the dog too.

That’s more than enough doom and gloom for now, I think. Moving on to some positives, let’s focus on what can be done to solve this parasite problem.

How Can We Treat Lungworm?

It’s good news, friends. Lungworm can be effectively treated! As long as you catch it early enough, there’s an overwhelming chance that your hound will survive the infection and live a long and happy life by your side.

Another fantastic bit of news is that treatment for lungworm doesn’t even require surgery. It’s combated using a course of medicines that kill off the parasites from within, leaving your pooch fighting fit.

Lungworm Prevention

Prevention is always better than a cure, so let’s discuss some ways in which you can circumnavigate this nasty parasite altogether.

- No Interaction with Slugs or Slime – Let’s start with the obvious one. Do not under any circumstances allow your dog to go anywhere near a slug or its trail.

- Supervised Garden Time – Don’t allow your dog to chew grass or drink from puddles. Stop them from sniffing foliage and picking up sticks. If you’re aware of a recent slug presence, it may even be best to avoid the garden altogether.

- Slug Traps – If the slugs are making themselves at home in your kitchen and living room as they are in my house, invest in some preventative methods. Want a pro tip? Slugs love beer. They find the yeast irresistible, so pouring some out into a tray near their entry point is like a siren to sailors. A warning, though, this isn’t a humane method. The slugs will die in the beer – but what a way to go.

- Avoidance – Unsure where their entry point is or the beer trap not working? Make sure you keep your dog in a different room overnight.

- Stay up to Date on Worm Treatments – This is essential anyway.

- Clean up Dog Mess – Larvae end up in dog mess, so take it out of the picture.

- Slug Pellets – Your first thought may be to rid your yard of this slimy problem altogether with a generous scattering of slug pellets; however, most have a high metaldehyde content. Metaldehyde is extremely toxic to dogs, so you’d be solving one problem only to cause another.

Don’t worry, fellow slime warriors; why not try one of these safe alternatives?

- Seashells and Eggshells

- Coffee Grounds

- Copper Tape

- Nematode

- Diatomaceous Earth

- Recycled Wool Paste Pellets

- Corn or Wheat Bran

- Slug Repellant Plants

I personally think the best option is to buy specialized dog-friendly slug pellets. This bag of Ortho Bug-Geta Snail and Slug Killer is one of the best pet-safe options on the market at the minute.

The Geography of Slugs

I believe one of the biggest enablers of lungworm infection is that people just don’t understand when or where they’re at risk, so I thought it would be a good idea to discuss the threat geographically across the English-speaking nations.

This way, you can assess the level of localized danger to your pup and prepare yourself accordingly.

The United States and Canada

As it stands, there are no known toxic slugs in the USA or Canada, but the common garden slug still carries the lungworm larvae, so in early spring, when the weather is mild and wet, there is a high risk of infection.

Remember when I mentioned that certain sea slugs are poisonous to dogs? Well, some of them can be found along the coastline of the U.S., so keep your wits about yourself when going for a day at the beach.

Canada is a mostly cold region, with temperatures only rising in certain densely populated areas, so the risk of infection is never as high as in the States. Slugs don’t particularly enjoy the cold, especially when it’s snowy. That said, slugs won’t necessarily be killed by frost, as they can be hardy critters.

The UK and Scotland

The wildlife in the UK and Scotland is decidedly mild, unlike Australia and certain places across the U.S. As such, no toxic slugs exist, but they can still carry the lungworm parasite.

Infamous for their drizzly weather, our friends over the pond face a very high risk of infection come late April or early May when temperatures start to rise before summer.

Canine lungworm infection is still a fairly rare diagnosis in these parts of the world, but vets have noticed a significant increase in cases across the south of Wales and in Scotland too. This is mostly because there are more slugs due to excessive rainfall.

Australia and New Zealand

Despite the incredibly arid climate, Australia and New Zealand are hosts to a variety of weird and wonderful-looking slugs. Yet, as far as I can tell, none of these garden variety slimmers are toxic. But do they carry the lungworm parasite?

Unfortunately, yes, they do. Endemic in the warm tropical zones of Australia, especially in urban areas such as Sydney and Brisbane, many city-dwelling doggos are in danger.

There isn’t as much information about lungworm hotspots across New Zealand, but being that the poor young man that ate a slug on a dare lived in NZ, I’m willing to bet it’s pretty prevalent there too. As their climate is very similar to Australia, albeit slightly cooler, I wouldn’t be surprised if dogs in warm urban areas are most at risk.

We’ve all heard horror stories about Australian wildlife, from spiders as big as your head to box jellyfish. For the most part, New Zealand’s critter population isn’t quite as deadly, but both nations are home to a bunch of those poisonous sea slugs I mentioned earlier. In fact, they have three different incredibly toxic species of sea slugs lurking in their reefs and rock pools.

Nudibranchs

These things are so far detached from the grim garden variety slug we’ve become accustomed to. If I’m being honest, they’re downright beautiful. Often multi-colored and with angel-like appendages, they can be enticing to humans and dogs alike, but trust me, stay away from them.

Usually inhabiting coral reefs, rock pools, deep waters, or on land near an ocean, many Nudibranchs exude a toxic compound as a natural defense mechanism against predators.

Others aren’t actually poisonous, yet they’ll use their bright-colored bodies to communicate that they might be, keeping predators at bay. That said, it’s best to avoid them altogether, as even these non-toxic sea slugs can pick up toxins from surrounding sea life, such as sponges.

Elysia

Much like their cousins, the Nudibranchs, Elysia sea slugs consume certain sea life to imbue themselves with toxicity. Naturally, they’re almost completely harmless. It’s only due to their algal diet they’re able to ward off predators.

This instance of triple teamwork between sea slugs, algae, and toxic bacteria is some of nature’s first-ever recorded three-way symbiosis.

The level of toxicity that an Elysia slug can utilize against would-be prey isn’t known, so it’s unsure whether they could be fatal if ingested by a dog, but it’s best not to take any chances. If your pooch has become enamored with a green slug near or in water, get them as far away from it as possible.

Pleurobranchaea Maculata

More commonly known as the gray side-gilled sea slug, Pleurobranchaea Maculata slug sightings have become increasingly common along the coast of New Zealand, especially Auckland. Several dogs fell prey to its toxicity in a single summer.

It’s believed these unfortunate cases increase in the summer months as the warm weather brings them from the depths to the shallows, then the warm water loosens their grip on the substrate. Ultimately, they wash up on the shore, where dogs can sniff them out and, in some cases, consume them.

The toxin they carry is Tetrodotoxin (TTX), which is incredibly deadly. If you feel like you’ve heard that word before somewhere, it’s because it’s the exact same substance found in pufferfish. This stuff isn’t just harmful; it’s 1200 times more powerful than cyanide.

There’s enough of it in a single pufferfish to kill 30 humans. 1 -2mg is considered the lethal dose for a healthy adult human, so a single slug is more than enough to kill a dog.

The Gray side-gilled sea slug is shaped roughly like a mouse and is easily identified by its gills. If you have reason to believe your dog has been poisoned by one of these slugs, you need to get them to a vet ASAP. TTX is so toxic it can even cause paralysis, so if your dog is having trouble moving or breathing, you need to act fast.

My Dog Has Eaten a Slug. What Should I Do?

I know it can be a stressful situation, but if your dog has eaten a slug of some kind, it’s essential that you remain calm. Keeping a cool head can be difficult when you’re worried about your furry family member, but remember, poisoning or infection from eating slugs is a rarity.

Take this study carried out at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, for example. It states that out of a huge number of slugs and snails tested across the entire Glasgow area, only 6.7% of them tested positive for lungworm infection. This figure will fluctuate from place to place, but it’s still comforting to hear.

Your first port of call should be to book an emergency appointment with your vet. Don’t wait for symptoms to develop, as you may not notice physical evidence of lungworm infection for months.

Final Thoughts

Slugs themselves may not be toxic, but the fact that they’re an intermediate host for lungworm makes them a threat to the wellbeing of your pets, so do all you can to keep your all-fours family members well away from them.

The information in this article was accrued via my own research, but I’m not a veterinarian, just a concerned dog parent. I highly recommend paying your vet a visit if you want confirmation of these details or extra info on the topic.